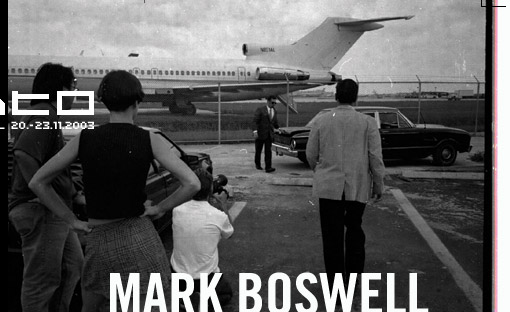

Welcome to the K-Zone Attention: The revolution will be televised. And if you're lucky, your head won't explode as you watch. The director of this hyperreality show will be Mark Boswell, and the events will unfold at a theater nowhere near you but in the scurrilous mind of its maker, downloaded directly into your subconscious. This is the kind of thing Marshall McLuhan warned us about. Welcome to the K-Zone Republic, the mythical Caribbean island created by Boswell and given a sort of half-life in his phenomenal first feature-length film, The Subversion Agency, a project begun nine years ago in Miami and finished several weeks ago in San Francisco. The film premieres as the main attraction on Friday night of the Florida Moving Image Archive's third annual Rewind/Fast Forward Film and Video Festival. But for Boswell, it also represents a triumphant homecoming for the pioneer of Miami's independent art film community during the 1990s. And the odyssey of the film's making is almost as remarkable and variegated as the film itself. It's a story that begins, well, at the beginning, with a Tallahassee-raised Boswell absorbing the strange and mysterious television shows of his youth (Man From U.N.C.L.E. , The Twilight Zone, Alfred Hitchcock Presents), eight years living and vagabonding through Europe with visits to communist East Germany, developing an appetite for counterculture literature, and finally landing in predeveloped Miami Beach in 1992. All of these influences have found their way into his films. "When I got into East Berlin, it was like crossing over into another world," says Boswell of his visit behind the Iron Curtain. "That really affected me, it was like a cleansing of the urban aesthetic without all this advertising, billboards, without all this extreme consumerism. It just reduced the city to the fragment of the shells of architecture. And it was really a great feeling. Plus the remoteness of the culture, the way everyone was distant, unfriendly, even rude. I really enjoyed it." Back in the States, Boswell was intrigued by the burgeoning art scene on Miami Beach at the start of the Nineties and volunteered to help with the Alliance Cinema's new film and video co-op, only to find himself running the show with fellow founder William Keddell. With the co-op formed and camera and editing equipment procured, an independent film community grew up around him and Keddell, who rented out equipment and taught courses on everything from film editing to documentary production. "He was hugely important," says Barron Sherer, archivist for the Florida Moving Image Archive and former Alliance Cinema account manager and programmer, of Boswell's influence on Miami's independent film community in the Nineties. "At that time, I think it was like 1993 when the co-op started, that's all there was. This was low-fi, low-tech, artist-heavy work that came out of the co-op. I think it was a Zeitgeist really." If Boswell was a catalyst at the right time and place, the facilitator of art-film dreams for a community of budding auteurs, he was also able to harness the resources of the co-op for his own film projects. And besides all the equipment to make short films, like his update of Ernest Hemingway's short story The Killers, he had a built-in film crew of actors, camera operators, and art directors. And then there was the South Florida setting that plays so prominently in creating the otherworld feel of his films, particularly The Subversion Agency. "Miami the Beach, and Miami at large, was really to me like a giant film set," says Boswell from his office in San Francisco. "Especially South Beach with the plethora of Art Deco architecture, which has that austerity. It's extremely elegant, and yet it's very tough, and it's even cold in a way, the sharp lines, the industrial sterility of it. At that time there were a lot of hotels on South Beach that were just empty, and I used to film in places like that." It's an aesthetic that calls forth the strange worlds created by William S. Burroughs, one of Boswell's main literary influences, with their bleak, bizarre environments and anarchistic governments. Using black-and-white film for nearly all of his projects, Boswell avoids obvious shots of contemporary fashions and technology in order to create a timeless world inhabited by wandering souls oppressed by an unseen hand, who also tend to be lawless and unpredictable. So it's only fitting that The Subversion Agency was financed by one slightly degenerate old friend from Boswell's caddie days on the European pro-golf tour, David Maurice Letourneau, a man who went from owing Boswell $200 to a $100,000 inheritance. When the skeptical Boswell saw the two Porsches parked in his friend's garage, he knew the financing offer was for real and immediately went to work on the film. "Because I could see this stuff going to Vegas, whatever was left outside of the Porsches," says Boswell of his desire to seal the deal. He assembled a cast from the characters he'd met through the co-op: Black actor Larry Robinson and his deep baritone voice served as the film's narrator, wife Susanne Naugebauer played a seductive translator, grim-faced Jock Mitchell a CIA covert operative, and various bit parts and cameos went to Keddell, Paul Berry, and a man known as Robert the Rabbi. For the lead role of arms dealer/golfer Pierre Kozlov, he ran into childhood friend Gregg Shumann, who happened to ask, "So when you gonna use me in a film?" The exotic-looking Shumann, of no obvious ethnic descent, fit to a T the unfixed locale and ambiguous time of the film. After two weeks of guerrilla filmmaking, which included scenes shot in the empty pool of the Beach's Albion Hotel while the film's art director, Ben Wolcott, distracted the security guard, the film was edited down to 30-plus minutes. As it was too short for a feature, Boswell began incorporating archival footage in collaboration with Sherer, who would send clips of archived material and other interesting footage he came across. "Barron Sherer had come up with some ideas for a feature project, and one of those ideas is that he would shoot a character and then cut to an archival scene that would reference the character that he actually shot," says Boswell. "I started to think about that concept, and at the same time he started providing me with a lot of material." After moving to San Francisco in 1997 and taking a job as manager of the new genres department at the San Francisco Art Institute, Boswell continued to work on his film as time and money allowed; he pieced it together with clips here and there, including film he shot while visiting Cuba over the millennial switch. He also continued to create other short works and media art projects. His recent successes, especially in Europe where his work has been well received, include the short films Agent Orange and U.S.S.A. But it's with The Subversion Agency that his work has taken a revolutionary leap. Reminiscent of Godard's Alphaville and the experimental films of Bruce Conner, and with film and editing techniques inspired by the late co-op member and B-movie maven Doris Wishman, the film defies categories. "You can trace his evolution from his early stuff, but this one is just out there, man," says Sherer. "From our perspective we're really excited because it's probably the most creative use of material from our collections that I can think of in the ten years that I've been here. He's cutting back and forth between what he shot and vintage Miami, vintage Cuba, to make the K-Zone. It's trippy." Difficult to describe, with its often hallucinatory narrative woven together with archival footage as disparate as scenes from the Cuban revolution, police riot training film, and early Eastern Airlines ads, the movie has a visceral effect that demonstrates how powerful film and images can be when they're artfully juxtaposed. With both film and footage in black and white, it's sometimes difficult to tell where the movie stops and the archive begins. But then again, in the K-Zone, past, present, and future seem to be one and the same. "It's a mythical place, and it existed in my imagination, and it really exists in Miami itself because Miami is its own world, there's nothing like it," says Boswell. "That's what I love about it. It's seedy, it's corrupt, it's hot, it's unpredictable, it's mercurial, and it's completely anarchic. There is no fucking law in Miami." If the communist island created by Boswell looks oddly familiar to a South Florida audience, that's because much of the film was shot on locations in Miami and Miami Beach, as well as modern-day and revolution-era Cuba. But it's the intelligence and subtle satire aimed at politics both local and international that should have viewers nodding with recognition, which makes Miami the ideal place for its christening. (originally published in Miami New Times on July 10, 2003) Read more... |

The Subversion Agency will be screened at the Kiasma Theatre on Saturday 22 November at 15.30. Director Mark Boswell presents the film. |